Video 1: Linear economics

This video ends with a question: We cannot maintain this “take-make-away” model. What is the solution?

Ask students to share their answers by writing them on the flipchart for all to see.

Some key points regarding the workings of the economy:

- We live in a modern, advanced, global economy that provides benefits to many people.

- The Industrial Revolution raised the standard of living for many people around the world through mass production and consumption.

- There are obvious downsides i

n the video such as multiplying waste and the pressure on finite resources and raw materials despite technological advances.

Video 2: Recycling

This video ends with the question: What would need to change to make recycling work better?

Ask your students to summarize the main points of the video to see if the video was understood.

- Apparently recycling is useful, but it is less effective with short-cycle products

- such as aluminum cans and other packaging. The problem is that small losses multiply rapidly over time. In the video, we see that it will take about 14 cycles before the entire current stock of aluminum cans is in the landfill. And mind you, with our ever increasing recycle ratio, we are nowhere near 90%. We will never reach 100% recycling, so there will always be material lost. So basically, recycling is just a stay of execution.

- Have students think further about the example – why would aluminum cans be easier to recycle than other products? Are most of the products students use simpler or more complex in composition?

Video 3: Using less

This video ends with the question: What would need to change in order to confidently start using less?

It’s an appealing moral notion to suggest that we can all change our lifestyles and make do with a little less. But everyone’s income comes from someone else’s spending. As a result, the video indicates that less use may eventually lead to a recession.

As with the previous video, when we look at the bigger picture, beyond the individual, you are met with surprising results. Moderation by one person is fine, moderation by all leads to problems …

Return to the question, “What would need to change in order to confidently start using less?

- Remember to take into account how companies operate. Is there a way to make sure the money keeps going around the system without depleting our resources? Perhaps the idea is to stop selling products and only sell how they work, for example, subscribing to a carpooling service instead of buying a car. And perhaps we could also ensure that the materials from these cars could be reused more easily.

- Advanced question: why can it be difficult for a politician to campaign for “Use Less”?

Video 4: More long lasting products

This video ends with the question: Can products that last longer help?

Discuss what are the challenges to making longer life products successful?

- We want new products, but we also want to be able to use the materials and components used in them for other purposes. To keep up with the latest technology, products that are likely to become obsolete soon – such as a cell phone – will need to be designed in a way that they can be upgraded and the materials used can be easily reclaimed. Perhaps products should have a defined period of use. In other words, they are expected to get a second life with someone else and eventually the materials will be reused.

- Products with longer lifespans may work, but there is a danger that they could lead to a decline in consumption and thus a decline in spending in the economy as a whole (affecting jobs and ultimately living standards).

- Advanced question: what would be the effect for businesses, workers, and government if products were designed to last longer?

Video 5: Produce more efficiently?

This video ends with the question: What would we have to change to use efficiency as a solution?

Introduce to the class that this question is called the “paradox of efficiency.

- From an environmental perspective, spending more on more stuff – helped by efficiency” – is not so good if the linear, “take, make, and discard” system is still used for that stuff. Finally, in this scenario, the “stuff” is still wasteful of finite resources and has associated negative “externalities” such as environmental pollution. So the impact per unit may be less, the overall negative impact still increases.

- But if the system were really effective – i.e., it worked well – then our stuff would be made in a way that ensures that resources can be reused over and over again. Using toxic-free materials and substances and powered by renewable energy. Efficiency within that system would be a good thing.

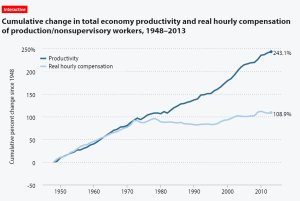

Source: Forbes Note the decoupling of wages from productivity which began around 1970.

From an economic standpoint, efficiency is not a problem as long as wages continue to rise along with them. Unfortunately, this is not the case in many countries with the result that loans have to close the gap between spending and income. But what happens if this credit goes away?

What people need is income, not just lower prices. If we could design a system in which materials and resources are reused over and over again, people could sell them to each other over and over again and make money by doing so.

Advanced questions :

- Why would it have an overall negative effect on the environment if efficiency goes up and prices go down?

- What is the difference between an efficient system and an effective system? And what should you actually go for?

Video 6: Green?

This video ends with the question: Although there are many green products in the right direction, what does the destination look like?

If this question is too complicated for your class, you may want to ask the following questions:

- What is the purpose of “green” products?

- Do “green” products always help us achieve that goal?

- Is it easy to make the “right” choices as a consumer?

- Can the “green” label help us choose, or must we become experts in each product to understand their environmental and social impact?

- Is it really fair that unless you can afford to pay more, you should choose unhealthy foods, harmful products and polluted skies?

- What if instead we changed the system so that all products were healthy for people and the planet?

- And how can we change the system? Well, that’s what we’re working toward….

Advanced questions:

- Are “green” products always good for the planet? Or are they often “less bad”?

- Are companies being hypocritical when they make “green” products in addition to their regular products?

Video 7: Fewer people?

This video ends with the question: How can we change things to also welcome the newest members of the human race to our planet?

The issue of controlling population growth is a tricky one. Given the projected population growth, we focus on how to welcome these new people despite the fact that they will increase demand which will ultimately consume more resources….

Encourage students to come up with a hypothetical: if we had a system where production and consumption were benign, why would we worry about the number of people?

Summarize and reflect:

What connects all the “eco-friendly” concepts we looked at in this lesson?

- They tend to look only at the short term, they can have negative economic effects and they are all isolated actions rather than looking at the whole system.

- We need to bring out the longer-term perspective, in a way that is still ok economically, but in which social and environmental factors improve.

- We could do this by learning from living systems, especially since these living systems have an impressive record of 3.8 billion years. The following video addresses this.

Video 8: Learning from nature

This video ends with the question: what are the rules for safe healthy production?

The different elements of the lesson all convey the idea that production and consumption can be looked at in a different way. Help your class draw conclusions from the lessons by applying what they have learned and have them consider why ants may be a good model for production and consumption. And to what extent is this different from how our system currently works?

Key points include:

- Their biomass is larger than that of humans, but their impact on the environment is positive.

- They are adapted to the system, i.e., all their waste is food for something else, they live off renewable energy, they are diverse in their functions, and they restore natural capital through, for example, soil reconstruction.

- They are an effective species (not just efficient) – they ensure that the whole system thrives, but also ensure that their own species survives.